‘The full impact of great tragedy is not immediate: it takes effect slowly. It lies in wait on the fringe of dreams. It wakes one with a start in the small hours. It can shake the confident and strengthen the weak, stop the clock, roll back the seas. It can give a new meaning to life, and an old meaning to death.’1

Tyrone Guthrie, from his essay on the production of Oedipus, 1954

Today is a sad anniversary, marking 50 years since the death of the revolutionary theatre director, Sir Tyrone Guthrie. On 15 May 1971, at the age of 70, Guthrie died suddenly of a heart attack while sitting in his chair at home, opening his bills. His death came as a shock to the theatrical world, but especially for my father, Colin George, for whom Guthrie had become an inspiration, a mentor and an ally in the battle to build the Crucible Theatre.

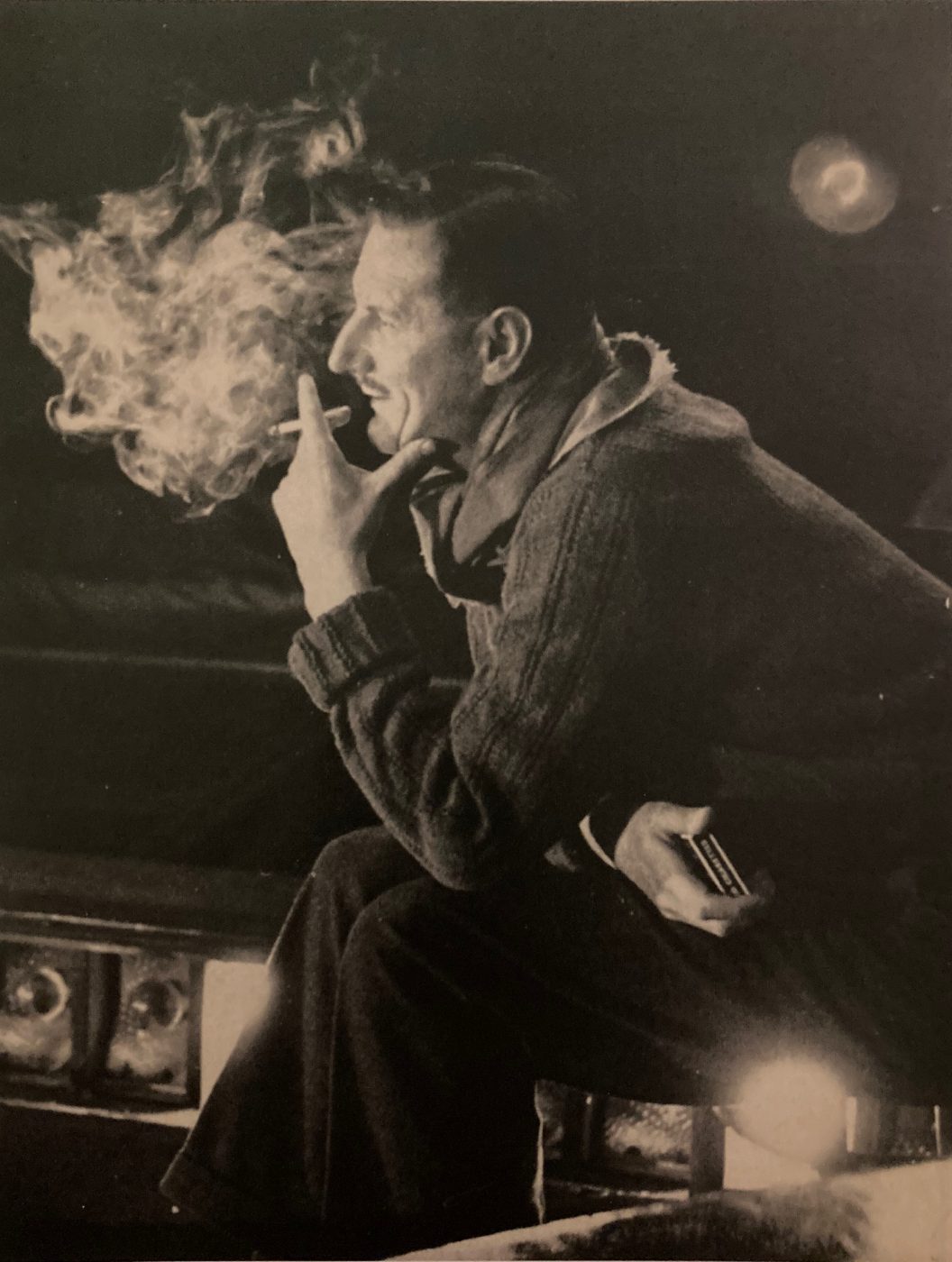

Tyrone Guthrie directing a show, early 1960s

By the time of his death, Guthrie was a towering figure of international theatre, with boundless energy and a sharp intelligence to match. Describing himself as ‘a very Irish sort of Anglo-Scot’, Guthrie built his reputation in the 1930s as a versatile director, scoring critical and commercial successes with his productions of Shakespeare, opera and plays by new or unknown playwrights.

Guthrie was committed to theatre’s important role in society, and he delivered his views with a razor-sharp, unexpected and irresistible sense of humour. His enthusiasm was infectious, linked as it was to a lifetime’s experience.

Guthrie was at heart an innovator and he was passionate about the thrust stage. This harked back to the times of Shakespeare and the Greek Classics, with the actors playing in the middle and the audience surrounding them on three sides. The thrust stage created a more intimate relationship between performer and spectator, who were much closer to each other than in a proscenium theatre.

But the thrust stage Guthrie created was not a simple copy of the Greeks or Elizabethans. It was a more radical re-imagining of the potential of the thrust, mixing the sense of shared ritual from Greek theatre with the buzz of the football crowd, where everyone is aware of each other’s presence and reactions as the drama unfolds.

After successfully experimenting with the thrust stage at the second Edinburgh Festival in 1948, Guthrie collaborated with the gifted designer Tanya Moiseiwitsch in creating a thrust stage for the inaugural festival in Stratford, Ontario in 1953. Encouraged by its success, in 1963 Guthrie founded what became the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis, which also had a thrust stage designed by Tanya. He served as the theatre’s Artistic Director until 1966.

When he met my father in Sheffield the following year, Guthrie was quite literally the ‘right man at the right time’. My father was Artistic Director of the Playhouse and the previous year Sheffield City Council had agreed that the Playhouse should have a new theatre. Discussions on its design were already advanced, but my father was unhappy with the proposed stage and wanted to break free from the ‘picture box’ proscenium arch and bring the actors closer to the audience.

‘You should see some of the thrust stages in North America’, Guthrie helpfully suggested. And when Guthrie thought something was a good idea, he knew how to make it happen.

The next day he used his considerable powers of persuasion to convince the Board of the New Sheffield Theatre Trust, and one month later my father and the new theatre’s future administrator, David Brayshaw, were on a plane to North America to start a ten-day whistle-stop tour of open stage theatres.

My father’s Damascene moment came on his first night in Minneapolis when he walked into the theatre’s auditorium and saw the thrust stage for the first time.

‘Suddenly there it was, through a doorway at the end: the stage. Gleaming polished wood, a narrow promontory jutting out into space, inviting the actor to stand on it and “ascend the brightest heaven of invention”. I cannot describe my feelings without waxing lyrical. It was the “tipping point” for me—a phrase that in hindsight defines the moment a revolution suddenly catches fire, or a battle is won or lost.’2

The Guthrie Theater auditorium as it looked in 1967

On their final night in Minneapolis, my father and David saw Guthrie’s production of House of Atreus, which was performed in Greek masks, with the Gods on 12-foot-high stilts, the ‘heroes’ on lifts and the rest of the cast barefoot. It was perhaps the most extraordinary theatrical experience of their lives, and one which convinced them of the impact that performers on a thrust stage could have on an audience.

In the final scene, Orestes is tried for the murder of his mother before the goddess Athena and the god Apollo. As Orestes knelt before Athena, my father saw Athena’s eyes look down on him. They actually moved.

Orestes kneels before Athena and Apollo in The House of Atreus, Guthrie Theater, Minneapolis, 1967, Directed by Tyrone Guthrie, Designed by Tanya Moiseiwitsch

Astonished by this technical trick, after the show my father asked the actor, Douglas Campbell, how it had been achieved. ‘Why don’t you see for yourself?’ he replied. Douglas took him under the stage to where the mask of Athena was hanging. And the eyes? They were painted on the surface of the face. They could no more have moved than the eyelids fluttered. It was the skill of the actor, and more important, the audience’s belief in that theatrical moment, that had blessed Athena with human eyes.

Guthrie’s House of Atreus would cast a long shadow over my father’s theatrical life and cemented his conversion to the thrust stage.

Back in Sheffield, my father and David proposed changing the theatre’s design to a thrust stage. Backed by Guthrie’s strong personal endorsement, the Board gave their approval and embarked on building what would become the Crucible Theatre.

Throughout the building’s design and construction, Guthrie maintained a strong influence. Guthrie introduced my father to Tanya Moiseiwitsch, who drew on her experience designing the thrust stages at Stratford, Ontario and Minneapolis to create her masterpiece in Sheffield. And when the design aroused opposition from conservative quarters and luminaries of the theatrical establishment, most noisily Sir Bernard Miles, Guthrie counter-attacked with vigour, dismissing the thrust stage’s critics as dinosaurs.

Guthrie’s creative influence was also strong on my father’s productions, notably the Playhouse’s first Sophocles, Oedipus, in 1968, the year after he saw Atreus, and his production of The Caucasian Chalk Circle the following year. Both productions had masks, actors on stilts and elaborate costumes (the latter was designed by Tanya). Guthrie even used his influence to secure my father directing jobs in Stratford, Ontario and Ottawa, where he was able to grapple with the technical challenges of directing on a thrust stage for the first time, ahead of the Crucible’s opening.

As planning began for the Crucible’s first season, Guthrie agreed to bring his production of House of Atreus to Sheffield, where it would open the theatre alongside my father’s production of Peer Gynt. In January 1971 Guthrie visited Sheffield to view the auditorium under construction (see the photo below).

Sir Tyrone Guthrie (left), Colin George (right) and Frank Hatherley (behind, Director of Productions at the Sheffield Playhouse) survey the shell of the Crucible auditorium under construction, January 1971.

That April my father visited Guthrie at his home in Annaghmakerrig, Ireland, where they spent the weekend trimming rhododendrons in the huge garden, reading plays and discussing House of Atreus and the Crucible. Later that month Guthrie started directing The Barber of Seville for the Phoenix Opera in Brighton, and they exchanged letters about the Crucible’s opening productions. But my father’s last letter to Guthrie on 12th May was to receive no reply.

Three days after writing it, my father was giving notes after the dress rehearsal of his final production at the Sheffield Playhouse, the musical Britannia’s Boys. He spotted the Stage Manager hovering around significantly, waiting for the Company to clear before coming up to him. ‘You needn’t tell me’, my father said, ‘the wigs haven’t arrived from London.’ ‘No’, he replied, ‘I have just heard on the news that Sir Tyrone Guthrie died this morning.’

My father never spoke about how the sudden death of Guthrie affected him emotionally, but it was a cruel blow to take. He had no idea that Guthrie had been so unwell in his final months and had read the comments in his last two letters to my father – lamenting that ‘the unrelenting high spirits of Barber of S are killing me!’ – as literary flamboyance. And now, suddenly, the man who had inspired my father to build a thrust stage theatre in Sheffield was gone, and he had to face his greatest challenge as a director without his mentor by his side.

Fortunately, the Company of the new Crucible Theatre rallied round and the actors who had been hired from Stratford, Ontario, among them Douglas Campbell and his wife Ann Casson, brought their experience of the thrust stage with them to Sheffield. But Guthrie’s absence at the opening of the Crucible that November left a psychological hole, and his ghost would haunt the theatre’s troubled opening season.

Design by Tanya Moiseiwitsch for The Persians at The Crucible, October 1972

In October 1972 – in what in retrospect looks like a ritual act of cleansing – my father opened the Crucible’s second season with his production of Aeschylus’ The Persians, designed by Tanya. This was a direct homage to the theatre Guthrie had inspired and the production of Atreus that never was.

But The Persians was not well received by the public or critics and marked the start of a crisis at the Crucible, one which would result in the departure of Tanya Moiseiwitsch as Design Consultant and my father’s resignation as Artistic Director, barely a year after the theatre had opened.

If you want to know the whole story, it’s all in ‘Stirring Up Sheffield: An insider’s account of the battle to build the Crucible Theatre’, which will be published by Wordville to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Crucible’s opening in November 2021.

For today, I tip my hat to the great Sir Tyrone Guthrie: mentor to my father and inspiration for the finest thrust stage auditorium ever built, Sheffield’s Crucible Theatre.

Notes

1 This essay is reproduced in the book Thrice the Brinded Cat Hath Mewed, Clarke, Irwin & Co., Toronto, 1955.

2 From ‘Stirring Up Sheffield: An insider’s account of the battle to build the Crucible Theatre’, which will be published by Wordville on 9 November 2021.