First published on this website on 24 August 2020

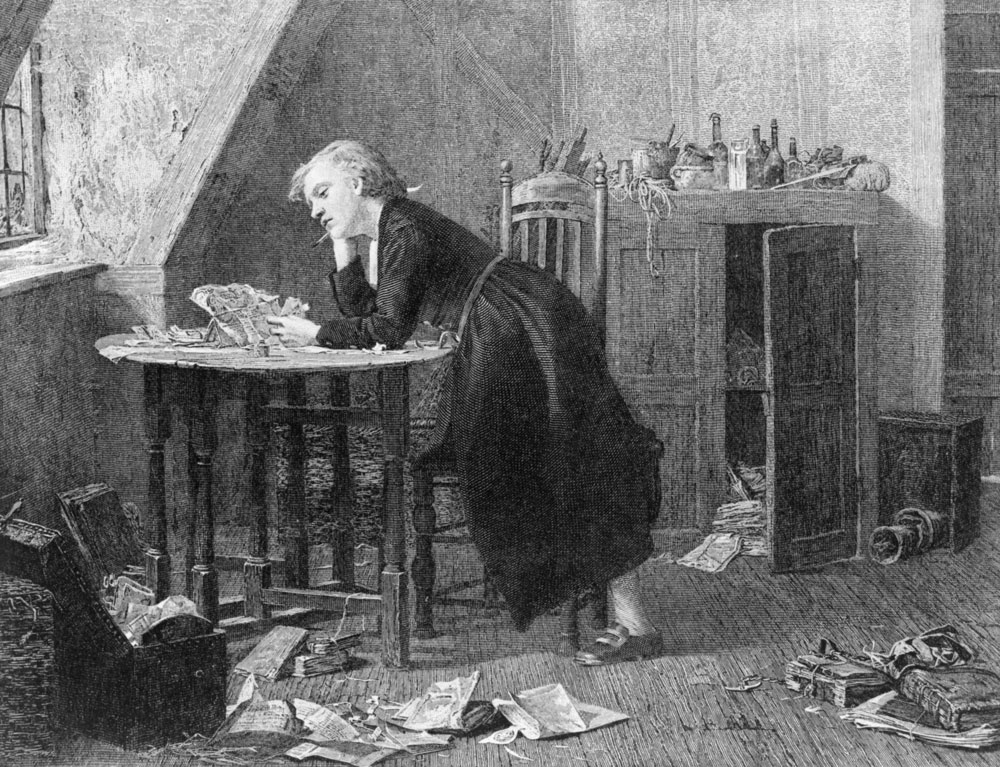

Today is the 250th anniversary of the death of one of the 18th century’s most extraordinary figures, Thomas Chatterton. He was a self-taught genius, a gifted poet, a scurrilous pamphleteer – and a fraud. But there was nothing shabby about Chatterton’s fraud, which was in equal parts mischievous, brilliant and subversive. His lonely death in a garret flat in Holborn two and a half centuries ago went almost unnoticed at the time. But in the years that followed his poetic creations stirred up fierce controversy, while the tragic manner of his death (was it suicide or an accident?) inspired a generation of Romantic Poets. It even led to Henry Wallis’s beautiful painting above, which you can see in Tate Britain.

So who was Chatterton, and why is he still remembered today? Thomas Chatterton was born in Bristol in November 1752. His father, the sexton of St Mary Redcliffe, had died four months previously and the young Thomas was raised by his mother, grandmother and older sister. But he was close to his uncle, who had taken over his late father’s role as sexton, and he encouraged his precocious nephew in his academic and literary pursuits, as well as giving him the run of the church. Inspired by illuminated music folios discarded by his father, the young Thomas taught himself to read and spent hours poring over old books, scraps of manuscripts and minuments (title deeds) hidden in his father’s wooden chest.

By the age of 8 Thomas was spending the whole day reading and writing in his attic, surrounded by old books and ancient parchments. By 10 he was writing poetry and the following year, at just 11, he started contributing articles and poems to the Bristol Journal. That year he produced his first piece of literary mischief, a pastoral eclogue entitled ‘Elinoure and Juga’ which he claimed dated back to the 15th century. The poem had in fact been written by Chatterton himself and carefully copied onto scraps of ancient parchment.

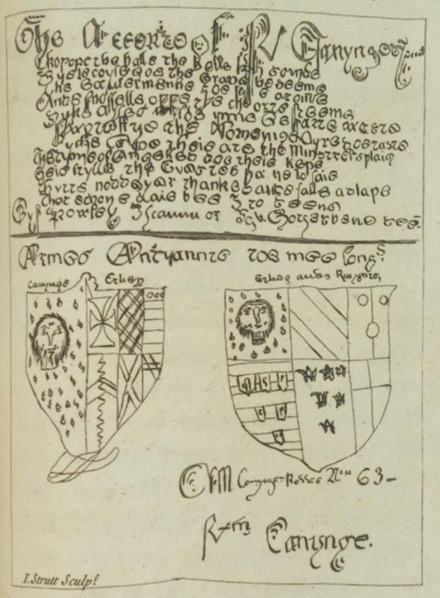

Chatterton’s success in fooling his superiors boosted his confidence and led to his greatest literary creation: Thomas Rowley.Thomas Rowley was supposedly a 15th-century priest, poet and chronicler from Bristol whose lost manuscripts Chatterton claimed to have discovered. In reality, Rowley was the creation of Chatterton’s imagination and over several years he produced dozens of poems and tens of thousands of lines of verse under Rowley’s name, all in pseudo-Middle English. Through Rowley Chatterton created a fantasy world of his own, populated by his heroes from Bristol’s 15th century, from the real William Canning (who founded St Mary Redcliffe) to the imaginary Thomas Rowley.

But Rowley was not just about literary mischief. For Chatterton, Rowley was a ticket to fame and patronage. On leaving school Chatterton had been indentured as a copy clerk to a local lawyer, John Lambert, who beat him when he discovered his apprentice writing poetry on the job, and Chatterton was determined to escape Lambert’s clutches and seek his fortune.

Chatterton first caught the attention of a local antiquary, William Barrett, and lent him several Rowley manuscripts from which Barrett quoted extensively in his ‘History and Antiquities of Bristol’ (much to his later embarrassment). Chatterton then offered other manuscripts to the London publisher, James Dodsley, but he declined, doubting their veracity.

Chatterton then upped his game and in 1769 he approached one of England’s leading writers and man of letters – Horace Walpole. Walpole was a shrewd target for Chatterton’s deceit as five years previously he had published the world’s first Gothic novel – ‘The Castle of Otranto’ – and he was known to be fascinated by mediaeval mysteries, having built himself a mock Gothic mansion in Twickenham. Walpole initially took the bait, offering to publish a selection of Rowley poems if they had not already appeared in print.

But it was a risky move by Chatterton, Because Walpole was highly sensitive to questions over authenticity having himself fallen foul of critics when he claimed in the first edition of his Gothic novel that the book was a translation of a 16th century manuscript he had discovered in the library of an ancient Catholic family. (In subsequent editions Walpole freely admitted he was the author.) When Walpole’s friends warned him that the Rowley poems were fake – and that their author was just 16 – he sent a cold rejection to Chatterton.

Walpole’s rejection hurt Chatterton badly and prompted a poetical retort, brimming with rage and satirical bitterness:

WALPOLE, I thought not I should ever see

So mean a heart as thine has proved to be.

Thou who, in luxury nurst, behold’st with scorn

The boy, who friendless, fatherless, forlorn,

Asks thy high favour — thou mayst call me cheat.

Say, didst thou never practise such deceit?

Who wrote Otranto? but I will not chide:

Scorn I’ll repay with scorn, and pride with pride.

Still, Walpole, still thy prosy chapters write,

And twaddling letters to some fair indite;

Laud all above thee, fawn and cringe to those

Who, for thy fame, were better friends than foes;

Still spurn th’ incautious fool who dares —

Had I the gifts of wealth and luxury shared,

Not poor and mean, Walpole! thou had’st not dared

Thus to insult. But I shall live and stand

By Rowley’s side, when thou art dead and damned.

Not long afterwards, Chatterton penned an ironic “Last Will and Testament” which so frightened his employer that he released him from his apprenticeship. Leaving his home town of Bristol behind him, Chatterton set off for London in April 1770 and plunged himself into his work. In a purple period of four months he produced a flurry of political pamphlets, poems, lyrics, operas and satires. He also continued to write Rowley poems in secret, although none were published in his lifetime.

But Chatterton was struggling financially and in June he moved into a garret flat in Holborn (on the site of the Holborn Bars building). His efforts to find a wealthy patron foundered, not helped by his abrasive political writings which put him on the wrong side of the political winds, and his punishing lifestyle – writing throughout the night and eating poorly, if at all – started to take its toll.

On 21 August while walking in St Pancras Churchyard, deep in thought, Chatterton accidentally fell into an open grave. When his companion helped him out and joked that he was happy to have helped in the resurrection of a genius, Chatterton replied: “My dear friend, I have been at war with the grave for some time now.” Three days later Chatterton was found dead in his garret flat. An empty bottle of arsenic and torn fragments of paper were found on the floor next to his bed. (The fragments were later found to be not his suicide note but a new ending to what is probably his masterpiece, ‘Songe to Ælla’.)

But – like so many celebrated artists – Chatterton’s untimely death was the prelude to his fame. Seven years later a collection of the Rowley poems was published by the eminent scholar, Thomas Tyrwhitt, who initially believed them to be genuine. This triggered 15 years of furious literary debate over the poems’ authenticity, which greatly raised Chatterton’s profile. It was eventually established that all of Rowley’s poetry came from the pen of Chatterton, and over the years an appreciation grew for his extraordinary talent.

In the following century Chatterton became the poster boy for the Romantic Poets, meriting eulogies from no less than Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth, Coleridge and Dante Rossetti. If anyone wonders where the cliché of the starving artist wasting away in a garret comes from, it started with Chatterton. He remains the prototype tragic Romantic poet and is, in all probability, the most referenced Romantic poet who hardly anyone has ever heard of.

But to me Chatterton has greater relevance today than solely as a poet. Because he is very much a modern figure, and one who is recognisable to the youth of today. There is so much about Chatterton that encapsulates the best, and the worst, of aspiring youth.

The first point, and one that I still can’t get my head around, is that when Chatterton died he was just 17. Seventeen! Not even an adult by modern standards. As an example of the genius, energy and exuberant creativity of youth, Chatterton is hard to beat.

Chatterton was also a rebel, and an audacious one, brazenly taking on the intellectual elite of the era with his fabulous creation. The way he hoodwinked them into believing his fraud puts me in mind of Chris Morris’s ‘Brass Eye’, which convinced our own era’s celebrity elite of everything from the dangers of ‘heavy electricity’ to the ‘nightmare of cake’, a new superdrug from Prague.

The manner of Chatterton’s death also mirrors the modern celebrity. At the time it was thought he committed suicide, but today it is thought more likely that he died of an accidental overdose of opium and arsenic (which was used as a treatment for venereal disease). Almost exactly two hundred years later – in September 1970 – the great Jimi Hendrix died of a drug overdose in a hotel in Notting Hill, five miles from where Chatterton’s garret had stood. As such, Chatterton forms part of a long list of artists who were lost far too young.

But Chatterton also had the weakness of many of today’s youth: he wanted to be famous and was prepared to perpetrate an elaborate fraud to achieve it. When he was a child, his sister asked him what image he wanted painted on his bowl and he replied: “Paint me an angel, with wings, and a trumpet, to trumpet my name over the world”. As a pamphleteer he held nothing back, writing inflammatory criticisms of leading political and royal figures – labelling the Dowager Princess of Wales ‘The Whore of Babylon’ – which were anything but ‘fact checked’. Viewed as a fame-seeking fraudster, he is almost a figure for our times.

And when it comes to peddling false narratives, Chatterton is in good company these days. Take two recent examples from our own century: first, Lance Armstrong, whose inspirational best seller – ‘It’s not about the bike’ (2000) – has been moved from the biographies to the fiction section of libraries. And second, James Frey’s ‘A million little pieces’ which made Oprah’s Book Club selection in 2005 only for the author to be hauled before Oprah the following year and forced to admit that many of the harrowing incidents depicted in his book had been exaggerated or invented.

Perhaps the most brazen attempt to subvert narrative authenticity comes at the start of the Coen Brother’s movie ‘Fargo’ (1996) which opens with the words: ‘The events depicted in this film took place in Minnesota in 1987’. Years later Ethan Coen admitted that the story had been made up, but he insisted that: ‘You don’t have to have a true story to make a true story movie’. Chatterton would have agreed.

So why am I so fascinated by Chatterton? I am no expert on his poetry and admit that I have struggled to read his dense pseudo-Middle English verses. But I am fascinated by his life and his passionate pursuit of his creative ambitions. I am inspired by his youthful energy, his unbridled creativity and his reckless courage to take on the so-called brightest minds of his generation – his ‘superiors’ – and run them a merry dance.

When they discovered his subterfuge they were furious, but I wonder if any of them paused to marvel at his extraordinary talent, however misguided it might have been. (Walpole’s involvement with Chatterton was to prove costly, as throughout the rest of his career he was dogged by accusations that his cold rejection of the young poet had driven Chatterton to suicide the following year.)

There is also much about Chatterton’s life as a writer that resonates with my own experience. He lived in a fantasy world he had created in his mind. As a creative writer myself, I get that. Last summer I spent two months writing the first draft of a children’s novel, my head full of talking owls, magical trees and invisible elves.

I also share Chatterton’s passion for history and ancient mysteries, which was embedded during my time at the King’s School Canterbury. Like Chatterton, I explored dark crypts and hidden passageways, discovering strange old books and fading inscriptions on tombstones. And like Chatterton, I was caught working on my own manuscript at a boring temp job (although I got away with a reprimand rather than a beating).

But it is the last four months of Chatterton’s life in London that resonate the most with me. Like him, I came down to London from Bristol (where I had just finished my degree) and struggled to become a writer, ending up in a pokey garret flat in Paddington. Wallis captures the atmosphere of the garret in his painting: the bed wedged into the gap between the window and the slanting roof, the bleak view over huddled rooftops.

It was a time of great creativity – I rewrote my thesis into my first book and also wrote my first report for the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), which I later joined. I remember the extraordinary concentration I could achieve, locked in the garret and writing away. But I also remember the bleakness, the shabby, depressing drabness of it all. And the periodic feelings of despair that I would never make it as a writer, that I would never get anything published. There is something for me about Wallis’s painting that captures the experience. And I can empathise with the anguish and rejection Chatterton must have felt in his final days.

Judged by today’s standards, Chatterton could be dismissed as a talented fraud. For despite his undeniable creativity, there is no escaping the fact that he deliberately tried to hoodwink the rich and famous of the day in an attempt to force his way into their ranks. But for me, Chatterton’s fraud is in a different league from the creation of false idols (like Lance Armstrong) or the stealing of millions from unsuspecting investors (here the list is endless).

Chatterton’s fraud was not to create a false version of himself, nor to pass off someone else’s work as his own. It was to create another persona – Thomas Rowley – through whom he could live out his fantasies in a long-forgotten world, play with the English language and stretch the boundaries of the authorial voice. Perhaps Chatterton found a creative freedom in Rowley’s ancient language and mythical world that he couldn’t in contemporary 18th century England.

In this sense Chatterton has much in common with another genial poet who only became famous after his death, Portugal’s Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935). Pessoa wrote under dozens of alter egos – heteronyms as he called them – which enabled him to explore all poetic styles and literary opinions, even pitting his heteronyms against each other in heated exchanges of letters in the press. Like Chatterton, Pessoa is still giving up his literary secrets years after his death.

The one thing I still cannot get over about Chatterton is his age. He died only three months short of his eighteenth birthday, having achieved more in his brief life than few of us could manage in a lifetime. I can’t help but wonder what kind of writer – and person – he could have become if he had had time to mature. Would he have pursued other writing ambitions, leaving Rowley behind as a curious footnote at the start of his brilliant career? What would he have made of the American and French Revolutions, which took place when he would have been in his twenties and thirties, and what role might he have played in shaping the debate? But the life he could have led is a blank slate, which is why he is just as fitting a tragic hero for the Romantics as he could be for our own generation.

Thomas Chatterton may have failed in his first bid for fame. But two hundred and fifty years after his death, he and Rowley are still remembered, discussed and eulogised, ‘standing side by side’ as he vowed to Walpole they would be. Chatterton was a flawed hero, it is true. But one whose flame burned so very bright, and all too briefly.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

If you want to read Chatterton’s Rowley poems for yourself, the complete works can be found on this website: https://www.exclassics.com/rowley/rwlintro.htm

The mysterious (.QE!.) has created a magnificent website about Chatterton, including scans of his original manuscripts and a wealth of information about the poet:

https://www.thomaschatterton.com

The Thomas Chatterton Society also has a wealth of information and events about the poet:

https://www.thomaschattertonsociety.com

The Bristol Central Library has an online exhibition featuring digital images of some of the Chatterton collection, including fragments of Chatterton’s poetry and his laudanum-stained pocketbook