Article first published in the Sheffield Telegraph, 3 June 2021

Fifty years ago, on June 26, 1971, the Sheffield Playhouse closed its doors for good, with a production that got tongues wagging and heralded an era of even greater risk-taking for Sheffield’s theatrical community. The last night at the Playhouse was a bizarre occasion—a performance of I Was Hitler’s Maid—written by Playhouse actor/playwright Christopher Wilkinson, with the up-and-coming Alun Armstrong in the lead role.

The play provoked juicy headlines in the press, with The Star newspaper warning its readers that the lead would be ‘Sheffield’s first full frontal nude male’. This failed to deter the punters. When the front of house manager stopped an elderly theatregoer from entering to save her blushes, she snapped back ‘Don’t tell me what I can and can’t do!’, brushing past him into the auditorium.

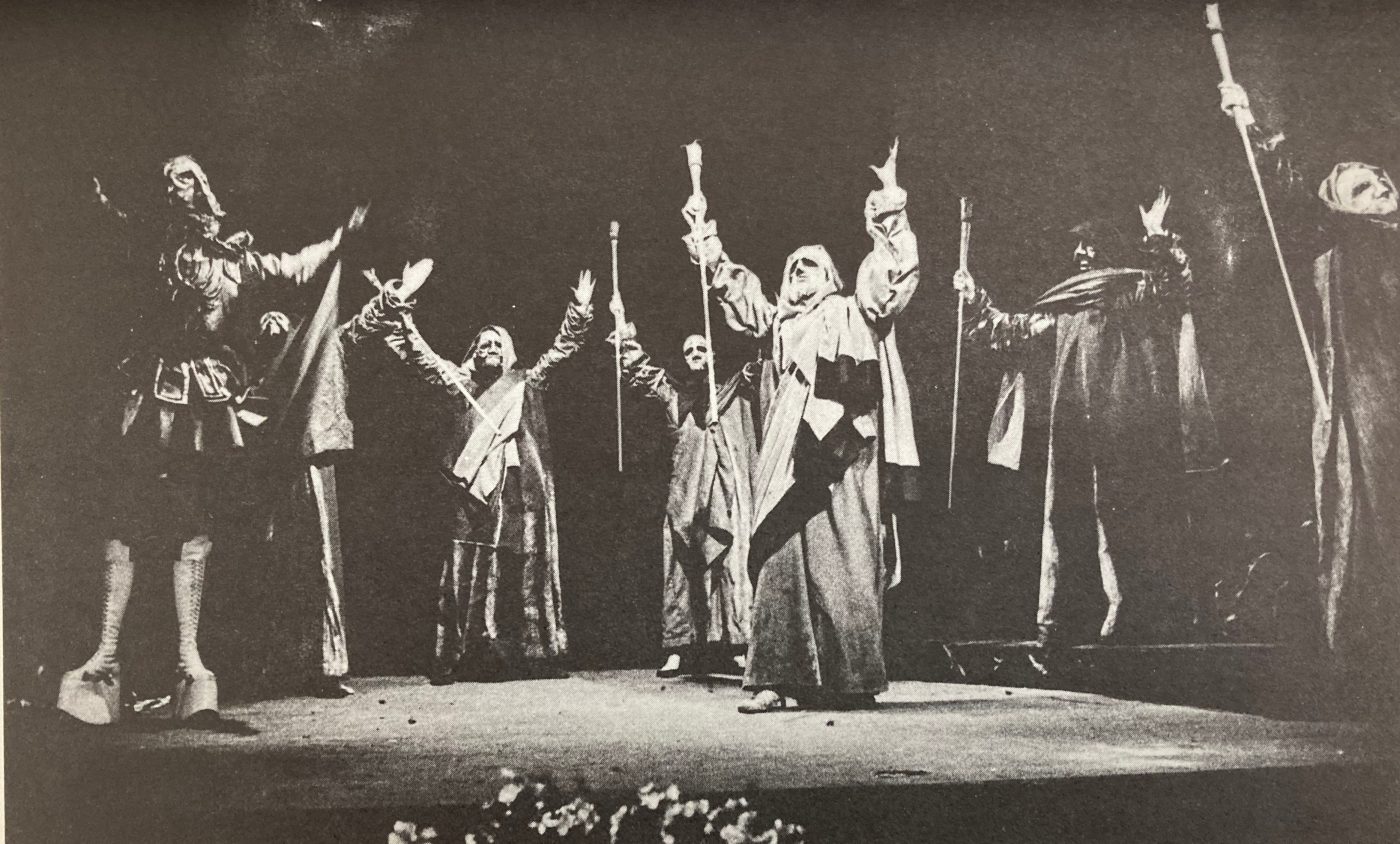

In the end, there was no Full Monty: the lead wore long johns throughout. But it was a strangely fitting end to the Playhouse and its final years of daring experimentation. Under the Artistic Directorship of my father, Colin George, audiences experienced Sheffield’s first professional productions of Pinter, Brecht, Pirandello, even Sophocles. Although these caused walkouts by some conservative patrons, they were matched by walk-ins by a younger generation of theatregoers who wanted a new kind of theatrical experience. The Playhouse exchanged directors and designers with theatre companies in Eastern Europe, most notably the Polish designer Józef Szajna, whose shocking designs for Macbeth (1970), including a skinhead Nigel Hawthorne in the lead role, wowed the Sheffield critics.

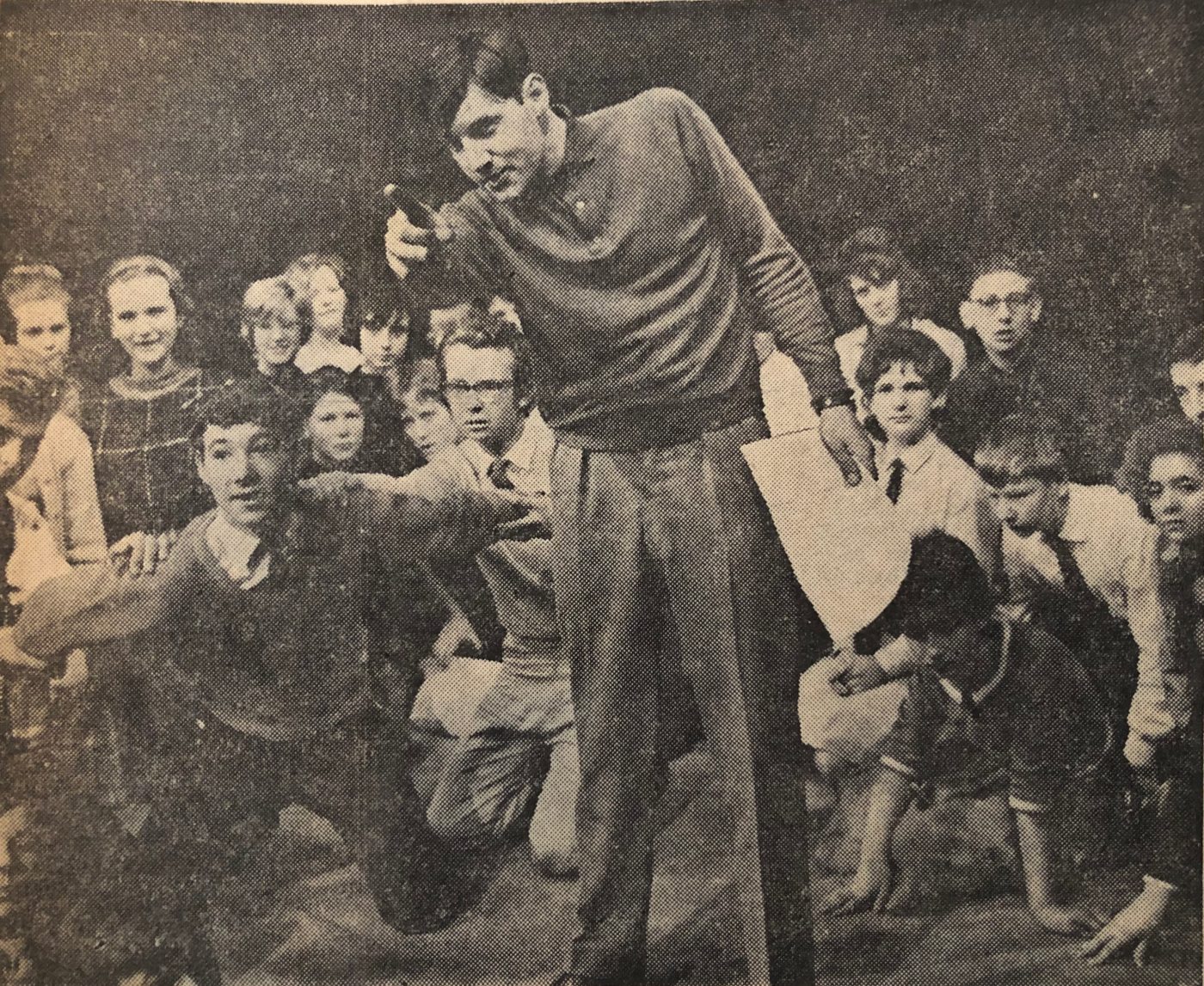

The 540-seat Sheffield Playhouse was home to one of the UK’s most forward-thinking theatre companies in the late 60s and its impact reached beyond the city limits. The Sheffield Playhouse was a pioneer in children’s theatre, teaming up with the Pegasus Theatre Club (founded by my mother, Dorothy Vernon) to host a Saturday morning drama club for students aged 14-18. With funding from the Arts Council, the Playhouse formed its own children’s theatre company, Theatre Vanguard, which toured schools with a troupe of professional actors— only the second of its kind in the UK and a model for many young people’s theatres that followed. The Playhouse also experimented with high-brow poetry readings and more relaxed jazz evenings, all aimed at bringing in a wider audience.

One show proved to be the high watermark of this era: The Stirrings in Sheffield on Saturday Night, by local playwright, Alan Cullen, with music by Roderick Horn. Since its first night at the Playhouse in May 1966, Stirrings has become part of local folklore and has been repeatedly revived, each time packing out the houses. One suspects that the decision by Sheffield City Council to build a new theatre for the Playhouse, which was announced one month after the first run of Stirrings ended, was influenced by the show’s rip-roaring success.

All of these elements of the Playhouse shaped what became the Crucible Theatre. New, experimental and unknown works remained a key part of the programme. And most importantly, the theatre complex was open to the public who could wonder in at any time, whether to buy a newspaper or get a meal in the grill bar. The way my father saw it, it didn’t matter if they just came in for a drink; one day, they would buy a ticket for a show.

By the summer of 1971, it was time for the Playhouse company to leave the Temperance Hall that had been their home for the previous 43 years. But this was not a moment of defeat, rather it was one of triumph. And they would take with them the Playhouse’s creative spirit, its commitment to the wider community and most of its staff (and even their furniture) to form a new company at the Crucible.